Exploring Food and History in Rome: A Conversation with Katie Parla

By Ian MacAllen on Tuesday, November 18th, 2025 at 4:27 pm | 1,226 views

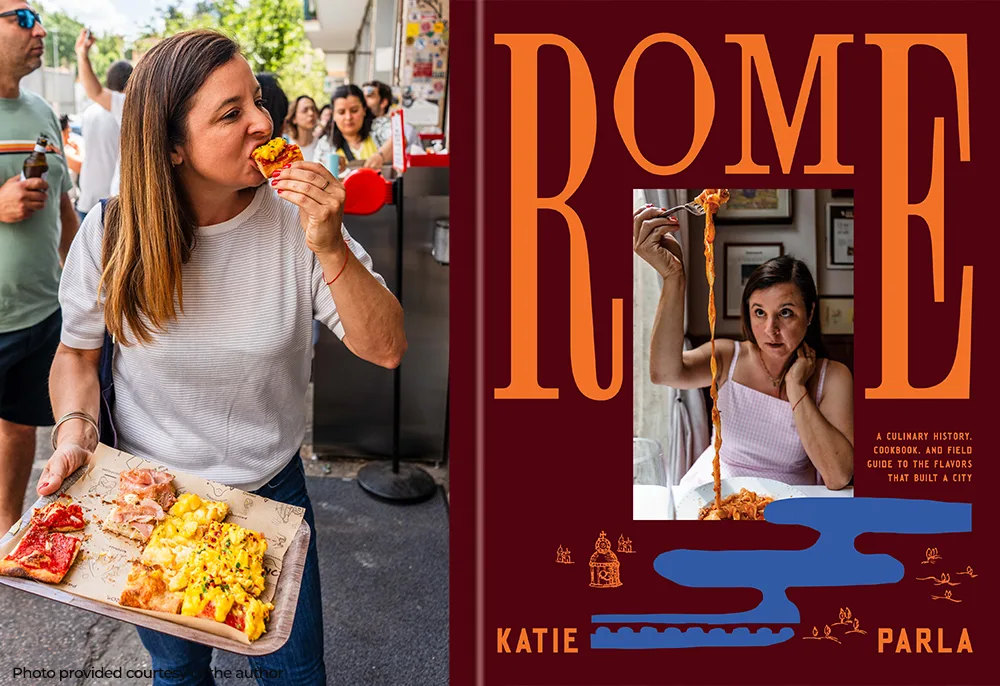

Katie Parla moved to Rome as a 22-year-old unsure of what she wanted in a career. She began writing about the food of the city, and built a walking tour business where she could show off the food, history, and culture. She’s now written eleven cookbooks and continues sharing her experiences through three-hour walking tours of Rome, where she introduces guests to delectable flavors, historical stories, and her favorite restaurants. In her newest book, Rome, she shares her collected wisdom, food narratives, and culinary history.

Rome in many ways is a natural progression of Parla’s previous cookbooks. In the 2019 book, Food Of The Italian South, Parla headed to Molise, Campania, Puglia, Basilicata, and Calabria regions to find local specialties and household favorites. Parla, who is originally from New Jersey, also took the opportunity to research her family’s origins in the region, eventually locating the house her great-great grandfather had once lived in.

In the following book, Food Of The Italian Islands, she filled in gaps consciously omitted from the Italian South, such as dishes from Sicily and Sardegna. I first caught up with Parla in 2023 to discuss that collection. In it, she explored Italy’s coastal cuisine, unearthing recipes and stories, and capturing stunning photos of shimmering fish and vibrant vegetables. She curated those recipes from two decades of traveling around Sardinia, Sicily, the Pontine Islands, and the Neapolitan Archipelago. Not surprisingly, the dishes are heavy on seafood–but also rabbits, offal, pork, fresh produce, and lots of legumes

In Rome, Parla has reassembled her team from Italian Islands, including photographer Ed Anderson and designer Ian Dingman, and together they have produced a new, stunning volume filled with rich culinary history, sidebars on titillating stories, more mouthwatering food photos, and recipes, both adaptations accessible to home cooks and those documenting more challenging local dishes. And for map lovers, Dingman produced beautiful, customized visuals to illustrate geography.

When I caught up with Katie Parla over zoom last week to discuss the book, she wore a knit cap with the word PAJATA embroidered across the front. The ingredient is one that home cooks in the United States might be challenged to source. Pajata (also known as pagliata), is the intestine of a suckling calf. Parla notes it’s hard to find outside of Rome, even in other parts of Italy, and so Rigatoni Con La Pajata might be one recipe you have to visit to eat.

However, I cooked up two less challenging recipes, the Pasta e Ceci, a simple peasant dish filled with complex flavors, and the Pizzette di Sfoglia, a tasty little snack ideal for any party celebration, finding the recipes easy and follow.

We chatted for close to an hour, and this interview has been edited for clarity and content.

***

RED SAUCE AMERICA: There’s a bit of history in this collection. You go all the way back to ancient Rome. What is the biggest influence that you take away from Roman history on the modern day?

KATIE PARLA: There’s a motif running through the book where it’s like a little Katie Parla cutout photo leading you around. I’ve been a guide in Rome for 23 years, and although I write books, I only do so because it’s a compulsion to write. My passion is guiding.

And so I would rather be out there in these streets talking about Rome’s pre-history to the present viewed through the lens of food, which is exactly what the first third of the book is devoted to.

I do three hour food tours or neighborhood immersions and we end up jumping back and forth between the Iron Age. We talk about fascism. We talk about contemporary food culture, because it’s physically impossible to eat for three straight hours.

Similarly, it is impossible to cook through all these recipes. Pajata is an ingredient which isn’t even available in the U.S. I write these books knowing that quite a few of the readers are going to be just reading and not actually cooking from the book.

Red Sauce America: You have a section on the Renaissance in Rome. When I think of the Renaissance, I’m more likely to think of Florence and Venice and Milan. What were the biggest impacts on Rome during the Renaissance era in terms of food and the markets and the guilds?

PARLA: Rome has a late Renaissance. Florence, Milan, Venice, and Naples were stable places with secular leadership that was really good at banking and interested in providing the conditions for economic growth. The church, however, had a 70-year period in the 14th century known as the Avignon Exile, in which the king of Rome and the papal states were in France.

And then for the next few decades, while everyone else is doing Renaissance stuff, the Pope is bouncing back and forth between France and Italy and other places. And so Rome is just the pits. The biggest impact is that when the Renaissance arrived in the mid-15th century, Romans finally had the economic stability to have more than the locally foraged ingredients on the table. They have access to more meat. And then the guilds are imposing standards, hygiene, and efficiency, and also clustering all the people in the same place. So if you’re going to the marketplace, you’re going to essentially two large places in Rome. If you’re going to get meat, it’s one major destination. And the caloric intake would have been increased significantly in the Renaissance period.

And then the variety of things, because Rome is growing. Rome’s population doesn’t grow because Romans are reproducing. It grows because of migration.

And so you have people coming from all over Italy, bringing new stuff with them. And this is even when some Southern Italian ingredients, the things that were under Spanish dominion would have entered. In the 1490s, the Spanish Inquisition led Jews to be expelled if they didn’t convert. And so this is probably when the artichoke comes to Rome. This is probably when the eggplant is introduced to Rome. Not that these would have been instantly embraced, but we do get a variety of foods through migration that was not the case in the medieval period.

Red Sauce America: What are the biggest shifts in Roman cuisine during the fascist period and World War II?

PARLA: During the fascist regime, food became a symbol of national unity. And when there were food shortages, abstaining from food became a point of national pride. If we look at certain propaganda campaigns, the idea of autarky, self-sufficiency, was one that was deeply promoted by the Duce and others.

It included the promotion of Italian wine, Italian grains, and ultimately Italian rice when it became clear Italian grains were insufficient to feed all the people. Also the idea that coffee could justify illegal invasions in East Africa, or was used at least in the propaganda, with deeply problematic African iconography was deployed in marketing during those periods in order to show the colonial connection to Ethiopia.

A lot of the things that we see as classically iconic Italian–like coffee, dried pasta, rice–these are regional traditions, for the most part. And then during the fascist era, they became these national symbols.

Red Sauce America: What is influential today?

PARLA: Roman cooks are influenced, until the late 20th century, by their grandparents’ cooking, which is often from Abruzzo or Calabria.

Today they’re influenced by the huge explosion of food television, by Gambero Rosso, Slow Food, and all the celebrity chefs. Even Joe Bastianich is out there on TV and slinging smashburgers at his eponymous chain restaurant. The people I know who cook are professional chefs, and then my friends who don’t cook–they really don’t cook. They buy stuff that’s already somewhat prepared, and then combine things and reheat it. It feels very much like the United States in the ’50s and ’60s, when brownie mix takes off because you have to just crack an egg and pour oil into it so it feels like you’re cooking. Italy is moving further and further away from its regional identities through mass media.

Red Sauce America: Do you see there being a risk that a lot of these traditions are gonna be lost if people are cooking at home?

PARLA: We don’t eat the same things in Rome that we did 30 years ago, much less 60 years ago. But everything is always an evolution. And a lot up until the past three or four decades of cuisine has already been lost.

But do we have to eat the way that we did in the past? I think it’s great if people eat more vegetables like they did back in the day. But also throughout the 20th century in Italy, most Italians didn’t eat very many calories, and they had very serious vitamin deficiencies due to poor diets.

Red Sauce America: Street food is suddenly extremely popular. You have a bunch of what I would describe as street food recipes in the book. Has the rise in popularity of street food generally changed the way Romans are eating?

PARLA: Absolutely. Over the past quarter century, we’ve had the arrival of the Euro that changed finances, the financial crisis, labor reforms, educational reforms, a whole wave of precarious work–the freelancer contracts. People have less money, people have less time. Now, everyone’s got a side hustle.

And even if you have the desire to cook, it’s not a given that you have the money or the time. So especially at lunchtime, Rome is not a city where you can go home. It’s not a city where there’s a culture to pack a lunch.

There’s a lot of street food. Sometimes it’s even marketed as “street-ah-food,” the S-T-R-I-T-F-U-D, because it’s both looking beyond Italian borders for influence. And you see this in a-million-and-one new food concepts popping up, as well as looking beyond Italy and looking beyond Rome. So there are Roman street foods like trapizzino, suppli, pizza by the slice.

Red Sauce America: When you’re building these recipes are talking to chefs about their recipes and adapting them?

PARLA: Not anymore. Definitely for Tasting Rome, I was in the kitchen all the time with people following them around and weighing stuff. If my recipe development didn’t really pan out, then I might inquire more.

This is my 11th cookbook, and I’ve just done so much recipe development in the past, I don’t need to be in the kitchen at all to write recipes. I write from taste memory. I write all the recipes, and then I go into the kitchen and actually see if my approximate quantities work out and make tweaks. Once everything’s dialed in, the recipe is good to go to the tester.

For the baking things, that’s a little bit more technical. I don’t develop all those recipes myself. I roughly develop the idea, and then collaborate with my friend, chef John Regefalk, baking genius, to really nail all the nuances because recreating Roman pizza dough recipes in your home oven, is not something that any Italian baker could tell you because they’re they’re working with like electric and gas ovens running at 650 degrees for pizza and I’m working with American home oven specs.

Red Sauce America: How do you balance practical recipes people can cook alongside the more complicated, more historical recipes that are really specific to Rome?

PARLA: Because this is independently published, I don’t have to listen to a New York editor saying: you can’t put this in the book, the ingredients are illegal. Pajata is illegal. You can’t even find pajata in most parts of Italy. It’s a Roman ingredient. Romans eat it. If any extra pajata is hanging around, it gets sent to Rome, the only market for it. But maybe there are half a dozen recipes where the ingredients are just not going to happen for most people, but it has to be a full document, right?

***

Rome: A Culinary History, Cookbook, and Field Guide to the Flavors that Built a City

Katie Parla

Parla Publishing

November 13, 2025

352 Pages

Available directly from Parla Publishing