Pizza’s Global Journey from Naples and Back Again: A Conversation with Luca Cesari, author of The History of Pizza

By Ian MacAllen on Tuesday, November 11th, 2025 at 2:36 pm | 1,808 views

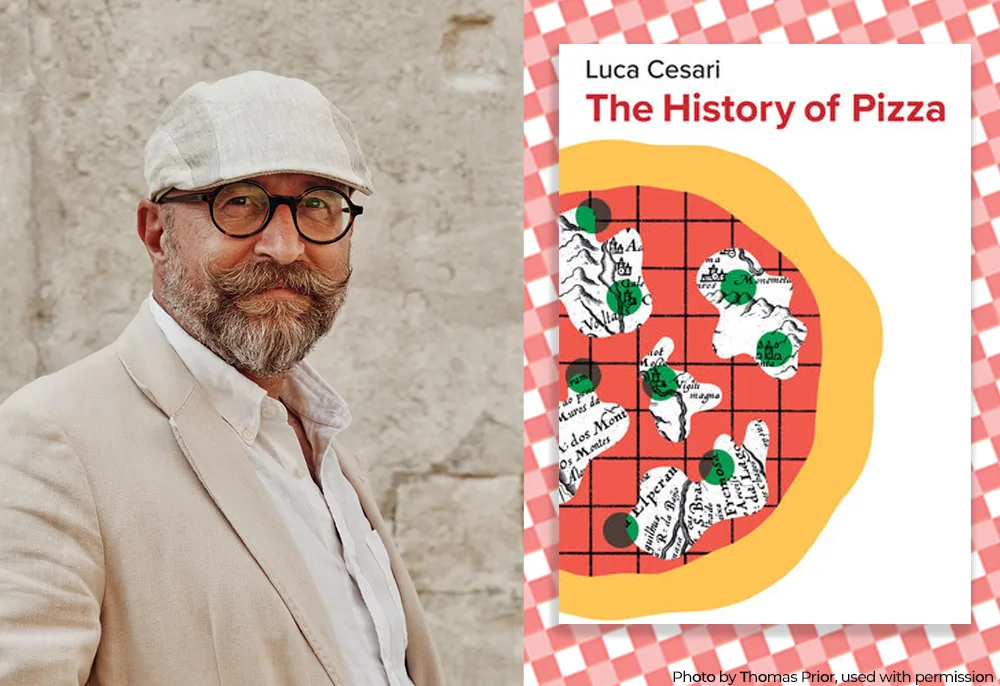

Historian Luca Cesari is an expert on Italian food. When his 2021 book, Storia della pasta in dieci piatti (The Discovery of Pasta in Ten Dishes) was translated into English in 2023, I reached out to him to discuss his research and the pasta he ate along the way. In that book, he looked at the origins of dishes like Fettuccine Alfredo, spaghetti al pomodoro, and other iconic Italian pasta dishes like lasagna, tortellini, and Carbonara.

When we finished our conversation, he mentioned the forthcoming Storia della pizza, which would first be published in Italian in 2023. I was especially intrigued since he mentioned referencing my book, Red Sauce: How Italian Became American in his discussion of American pizza.

Translated into English this year, The History of Pizza explores the origins of this iconic Neapolitan dish, looks at the migration of pizza to the United States, and the evolution of the dish from working-class flatbread into global sensation.

I reached out to Cesari earlier this month about discussing the book, and we correspond by email.

***

RED SAUCE AMERICA: The origins of Pizza Margherita are ambiguous. You present several possibilities, but remain hesitant to commit to a specific history. As a researcher, when do you decide that you’ve reached the end of a document trail? When do you decide there is going to be some ambiguity?

LUCA CESARI: Anyone involved in historical research knows that documents and sources often leave large gaps in our understanding of the past (more questions than certainties, in fact). Once a legend like that of the Margherita pizza is dismantled, reconstruction must rely solely on reliable historical evidence, which is never enough to fully clarify the truth. In my book, I gathered every available clue from period testimonies and newspapers to propose a plausible reconstruction, one that will hold only until new documents emerge. Unfortunately, the events surrounding the birth of the Margherita pizza were of little interest to people at the time, so accounts are extremely fragmentary. A historian must accept that not everything can be explained and, at best, can offer a reasonable hypothesis based on the evidence at hand.

RED SAUCE AMERICA: Do you have a sense when the Pizza Margherita became widespread, globally? For example, today, in New York City, it’s common to see a version of Pizza Margherita (tomato, fresh cow mozzarella / fior di latte, and basil) sold as distinct from a “regular” slice (tomato and low moisture cow mozzarella similar to scamorza), but this has been true only for the last decade or two.

CESARI: In Italy, there’s no such thing as a “regular slice” the way there is in the U.S. because any pizza with tomato and mozzarella is, by definition, a Margherita. The idea that this combination is just a “base” to which you add toppings like salami, mushrooms, or pineapple is a mindset that developed in America over the twentieth century. For a Neapolitan in the nineteenth century, a “plain” pizza without toppings was simply a round piece of flatbread: tomato and mozzarella already made for a rich dish.

The reappearance of the “Italian” Margherita in America over the last twenty years mirrors a wider trend toward ingredient-driven cuisine, where quality and sourcing matter most. Pizza has moved beyond the phase in which cheap tomato and cheese were mere carriers for other toppings, reclaiming their value as the stars of the dish. At the same time, the Neapolitan style itself has evolved in smaller pizzas, puffed crusts, lighter doughs, longer fermentations, and premium ingredients. The fact that the U.S. now recognizes two distinct Margheritas shows how deeply Italian and American food cultures continue to influence one another.

RED SAUCE AMERICA: Did the popularity of New York Style pizza contribute to the popularity of Pizza Margherita, as a more “authentic” variation of a “regular” pizza?

CESARI: Absolutely. When pizza first reached the U.S. East Coast between the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, tomato and mozzarella were not the most common toppings in Italy. They became standard in America mainly because those were the Italian ingredients most easily available. In Naples, people were still eating pizzas topped with garlic and fresh anchovies, or with cheese, or simply with oil and garlic.

Over time, American tastes and the global spread of pizza outside Naples helped standardize the Margherita as the “classic” flavor.

RED SAUCE AMERICA: You run through a variety of pizzas that are not really pizzas, including sweet tarts made of almonds and ricotta and pizzas made from pigeon meat. Many of these also have different dough, or are more like pastry. But today, especially in America, pizza has many different ingredients, condiments, and toppings. For you, what is the defining characteristic of pizza?

CESARI: We need to distinguish between “pizza” in a general sense and traditional “Neapolitan pizza” specifically. Abroad, only the Neapolitan style really took hold, but in Italy there have long been many regional pizzas, some thin and flat like bread, others tall and sweet like cakes filled with cream and strawberries. Once Neapolitan pizza left its native city, it naturally began to evolve through a century of experimentation. In America, numerous alternative styles appeared, inspired by the original but creating something genuinely new.

At this point, defining what makes a pizza is almost a philosophical issue: practically any baked dough with something on top can be called a “pizza,” but only a few deserve the name “Neapolitan pizza.”

RED SAUCE AMERICA: Some of the very local American varieties of pizza really stretch the limits of the American idea of pizza – things like Altoona-style pizza, Ohio Valley-style, and Colorado-style. Did you look into any of these hyper-local American creations? Are there similarly local variants found across Italy?

CESARI: The world of pizza is constantly changing, perhaps faster than any other branch of traditional food. Even in Italy, we’ve witnessed major transformations in recent years: from the renewed attention to flours, fermentation, and ingredients in Neapolitan pizza, to the rise of gourmet versions topped after baking with premium products. Abroad -especially in the U.S.- this creative drive has been alive for decades, producing countless local variations and enriching the concept of what pizza can be.

In my book, I focused on the more historically established styles rather than these new hyper-local ones, though they are fascinating. The historical side of the story already demanded a lot of space and research.

RED SAUCE AMERICA: Nordic countries have become one of the fastest growing pizza markets. The local cuisines are very different from Italy and the Mediterranean countries in general where pizza and other flatbreads are common. How are Nordic cuisines influencing and changing pizza?

CESARI: Pizza is a remarkably adaptable food, it integrates into local cuisines and creates a living dialogue with them. Stripped to its essence, pizza is a neutral base that can host virtually any ingredient, much like pasta. That flexibility is the real secret of its global appeal.

In Nordic countries, pizza has become a massive success, especially in Sweden, where the frozen pizza brand “!Grandiosa” is considered a national dish. Nowhere else have such eccentric toppings taken hold like ham, pineapple, banana, and curry, with a nod to tropical and Asian flavors. Time will tell whether these styles will influence the broader world of pizza or remain, as I suspect, isolated curiosities.

RED SAUCE AMERICA: In the post-war period, one factor that changed the way Americans ate pizza was the rise in gas-fueled ovens. Gas ovens in New York City really allowed for the rapid expansion of the city’s pizzerias since they were easier to maintain than specialty coal ovens. Did Italian pizzerias have a similar evolution in oven technology?

CESARI: Absolutely. In Italy, many pizzerias still use wood-fired ovens, but more and more are adopting modern electric models that guarantee perfect results while saving time and energy. Traditionalists dislike this shift, convinced that wood gives a unique flavor, but that’s really a myth with no solid basis.

RED SAUCE AMERICA: You mention the myth that the water in Naples is responsible for the special flavor. Perhaps not surprisingly, this myth is also often said about the water in New York City—to the point that pizzerias beyond the city’s borders attempt to replicate or even deliver it by truck. If not the water though, then why do you think cities like Naples and New York have pizza that is so difficult to copy?

CESARI: The average quality of pizza is indeed higher in places with a long-standing tradition and a dense network of active pizzerias, but that has nothing to do with the water, as I explain in my book. The real reason lies in the competitive yet collaborative ecosystem that develops among the key players in such markets. Just as in fashion or automotive industries, where horizontal and vertical expertise overlap and mature over time, these synergies raise the overall standard.

It’s not an easy concept to convey to the general public, especially when it clashes with long-standing marketing narratives about “authentic” local taste. Yet there are excellent pizzerias even far from traditional centers -some in the Far East, for instance- that have successfully reproduced or even elevated classic recipes.

RED SAUCE AMERICA: Beginning in the early 2000s, Neapolitan style pizzerias opened in New York City, especially Brooklyn, putting classic New York style pizza on notice. Sometimes the term “Neo-politan” has been applied to the dish, implying “new Neapolitan.” Do you think the arrival of the style in New York was the result of a renewed interest in “authentic” Neapolitan pizza, or was the fact that these shops opened in New York what caused the style to become more popular around the world?

CESARI: New York played a huge role in spreading tomato-and-mozzarella pizza as the global default and in developing its own distinct style. Later, the evolution of New York pizza diverged from what was happening in Italy, though the cultural dialogue never stopped.

The arrival of the “Neo-politan” wave represents a kind of reinfusion: a successful reinterpretation returning from Naples to New York. It’s likely that, once again, the U.S. will act as a launchpad for this renewed style, now viewed as more authentic and closer to the original.

***

History of Pizza

Luca Cesari

Polity Books

November 2025

230 pages